Computational protein design tries to solve the following problem: given the backbone structure of a protein, can we predict the amino acid sequence that would fold into this predetermined structure?

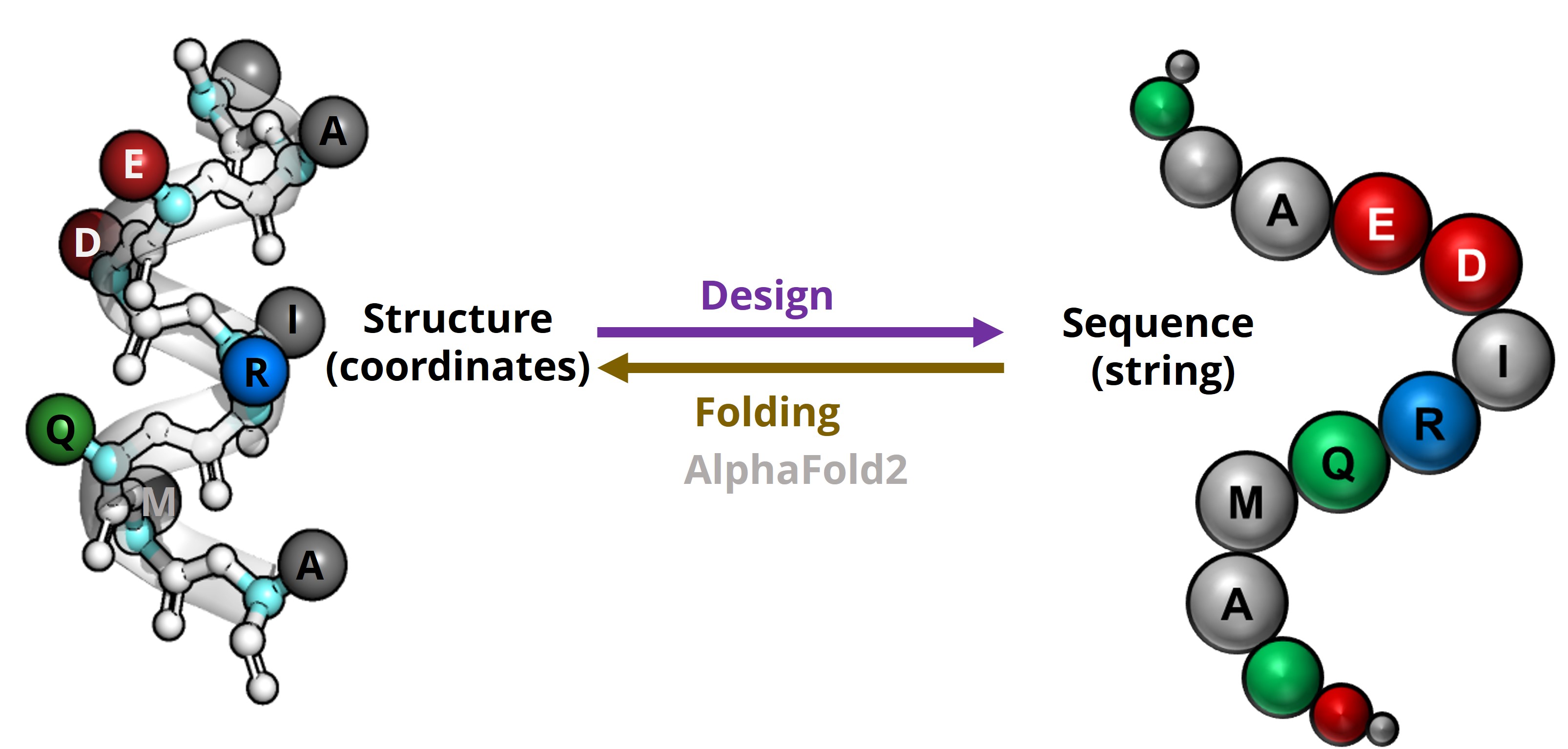

Protein folding v. protein design

To understand the design problem, we can first look at its close buddy - the protein folding problem.

The famous AlphaFold2

In 2020, AlphaFold2 came to fame by blowing every one out of the water in the 14th installment of Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) contest.

A nature news article quoted John Moult, who co-founded CASP: “In some sense the (protein folding) problem is solved.”

Most proteins have a defined 3D structure to do their jobs - a hemoglobin needs to be in a certain shape to carry oxygen around, and an insulin needs to be in a certain shape to bind receptors on target cells and tell them it’s time to take away the glucose in the bloodstream.

Experimentally, from a protein’s amino acid sequence, we can express/ synthesize the protein and measure its structure with X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and electron microscopy (EM).

Computationally, we want to predict the structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence directly - skipping the wet lab experiments all together, and this is called the protein folding problem. It’s been around for half a century, and significant progress was made by AlphaFold2 in 2020.

Mapping structure to sequence: protein design

In short, AplphaFold2 solves the folding/ structure prediction problem: given a protein’s amino acid sequence as an input, output the 3D structure of the protein.

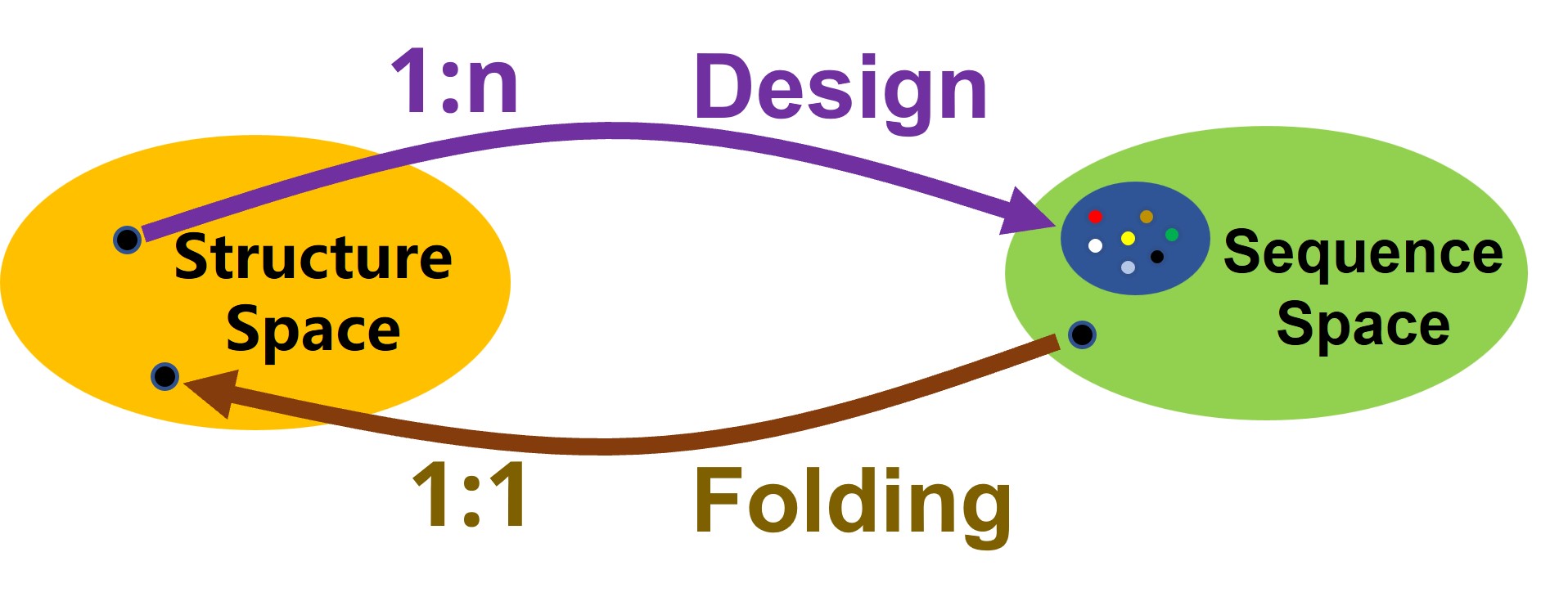

The protein design problem tackles this problem in the opposite direction: given the 3D structure of a protein, can we predict the sequence(s) that fold into this predetermined structure?

Computational protein folding problem maps an amino acid sequence (string) to a structure (coordinates of all atoms); whereas the design problem maps a predetermined structure to sequences.

It is worth noting that the folding problem is usually a 1:1 mapping, as most proteins have one stable natural structural state; whereas the design problem can be a 1:n mapping, as there have been examples of completely different amino acid sequences (evolved separately) folding into very similar structures.

Solving the design problem

The physical principle deployed to solve both the design and folding problems is as follows: proteins fold into the structure with the lowest energy/ potential.

Protein folds into a native state of energy minima. Source: wikipedia: folding funnel

So an intuitive way for solving the design problem is: for the given backbone, plug in/ try out each possible amino acid sequences, calculate the energy of that sequence, then find out the sequence that leads to the lowest energy.

The main problem with the brute force enumeration approach is that the number of possible sequence grows exponentially with the number of amino acids that make up the protein, and problems with exponential complexity are expensive to calculate.

Below is a subunit of insulin, it’s a small peptide of 50 amino acids long. Each residue position could be occupied by any of the 20 types of natural amino acid. The number of possible sequences would be 20^50, which is on the order of 10^65 - if it takes 1 second to calculate the energy of one sequence, it’ll take 10^57 years to go through all possible sequences!

There are many possible combination of possible amino acids at different positions for an insulin peptide.

Strategy to search the exponential sequence space

The main challenge of solving the design problem is that the possible sequence space grows exponentially with the number of amino acids, so it’s crucial to develop methods to efficiently search through the vast sequence space and find the low energy sequences.

A common work around is to Monte Carlo sampling (the old Rosetta design) or other statistically based method. Our lab adopts an entropy based probabilistic model.

Of course, the new and hot area of machine learning are providing promising models to solve the problem, such as the newly published ProteinMPNN model, which is a graph network.